Roman Climate Optimum and energy system resiliency

It’s quite easy to argue that modern civilization is much more robust and resilient than any ancient society, but consider how much of our critical infrastructure is written in memory unsafe languages

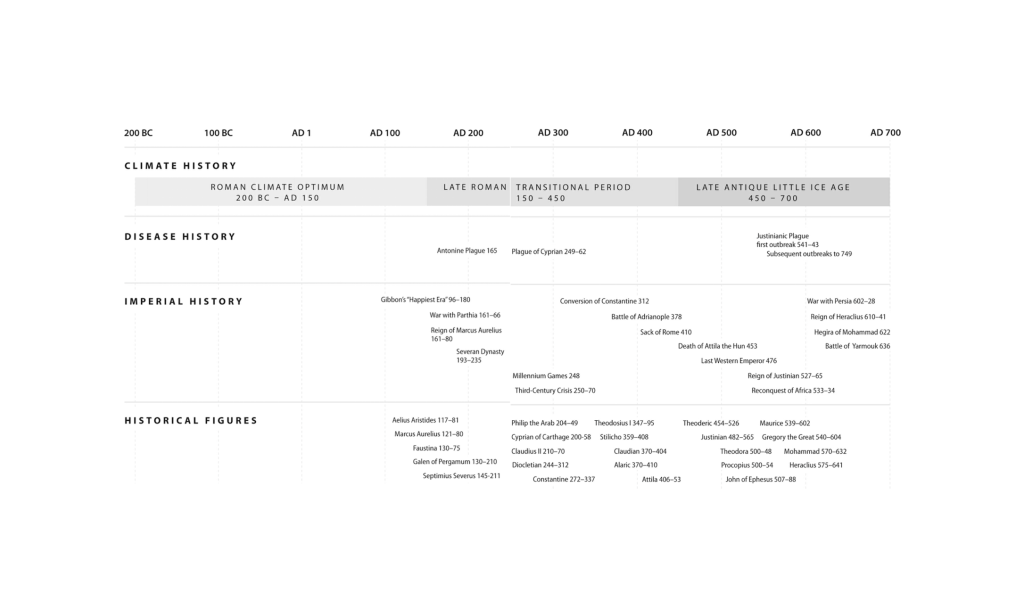

I just finished reading The Fate of Rome by Kyle Harper. The core thesis is that the Roman Empire suffered from the combined effects of volcanic eruptions, climate instability, and pandemic, which contributed to its collapse at the hands of revolution, invasion and institutional decay.

My takeaway is that no one thing “caused” the fall of the Roman Empire, but the internal, human-caused stresses like political infighting created vulnerabilities which were exacerbated by environmental factors.

Early on, the Romans were able to benefit from the Roman Climate Optimum, which was an unusually stable period of warm weather in Europe between 250 BC and 400 AD. The book goes into detail describing how it’s no coincidence that the Empire flourished during this period. Indeed, political problems, war, and revolution were regular features of Roman society, yet it was thriving.

As this period of calm came to an end, the resiliency of the system was hit by more extreme conditions, and pandemic in particular, which reduced the resiliency of the Empire.

Rome’s empire was always poised uncertainly between fragility and resilience, and in the end the forces of dissolution prevailed. But the supreme sway of climate and disease in this story relieves a little of the temptation to find the hidden flaws or fatal choices that spelled Rome’s demise. The fall of Rome’s empire was not the inexorable consequence of some intrinsic fault that only worked itself out in the fullness of time. Nor was it the unnecessary outcome of some false path that wiser steps might have circumvented. Long reflection on the fate of Rome led Edward Gibbon to marvel not that the empire had fallen, but rather that it “had subsisted so long.”

If you were sitting in Rome in AD 150, you would be looking back on several centuries of amazing progress. Maybe not a peaceful period, but certainly improvements in daily life, many technological innovations, and a growing empire. Yet the future wasn’t going to turn out so well.

The same could be said of someone sitting in London in 1910. The end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 brought a period of relative peace and massive technological development, but things also weren’t going to continue that way.

It’s quite easy to argue that modern civilization is much more robust and resilient than any ancient society. The likes of Steven Pinker have done a good job at documenting the vast improvements experienced over the last few centuries, and we have just demonstrated how technology can beat a novel pandemic (despite many failures and without a full accounting of the various social and economic costs). But what are the weaknesses few are paying attention to today?

As it’s such a central part of my life, our computing infrastructure stands out to me as an area of concern. I’m not so worried about the foundations – the underlying protocols are well designed and pretty robust – but knowing how most software is written doesn’t inspire confidence! This is particularly true when it comes to cybersecurity, an area where I don’t think we’ve seen a real catastrophe…yet. I particularly enjoyed my discussion with Thomas Ptacek on this topic last year. The growing popularity of strictly-typed memory safe programming languages is reassuring, at least until you consider how much software is written in unsafe languages like C!

Are we in our own “Roman Climate Optimum”? Has the time since 1945 been a period of relative peace with limited environmental catastrophe? The sun has been stable. We’ve had no major volcanic eruptions (Eyjafjallajökull not withstanding). COVID has been called a “starter pandemic” because of how much worse it could’ve been – we were surprisingly successful with the vaccine, but that was more luck than good planning. Are the systems of society sufficiently resilient to allow us to effectively deal with the next crisis, whatever it might be? Will we be able to adapt sufficiently to climate change?

How much we rely on electricity, and how precisely that system must be controlled, is another area where my interests overlap. Cybersecurity is particularly important for critical energy infrastructure. Electrification is a good step, but we’re stacking complex dependencies upon complex dependencies, and that doesn’t bode well for full system resiliency.

Back in 2019 I wrote about the risks from electricity system failure as one of the “medium likelihood / high impact” risks on the UK Government Risk Register. Of course, just a few months later we had a pandemic, which was also considered “medium “medium likelihood / high impact”. The average lifespan of a civilization is 336 years, so I find it interesting to consider what lessons we can learn about our own situation today.