AI's power problem: the slow grid

Near term, expect more self-provisioned power while transmission and substations catch up. Long term, nuclear is a perfect fit for data centers.

Headlines tout mega data center campuses (e.g. Meta’s 2GW Louisiana campus) as if they energize at full tilt on day one. In reality, these sites ramp over years, and the binding constraint is power delivery.

Obtaining GPUs is hard. Getting firm, timely power is harder. Grid incentives don’t match developer timelines - a point I made in a paper back in 2023:

[grid operators] are under a reliability obligation to provide energy to existing customers, which means they have a conservative approach to network changes. In contrast, data center operators want to bring on new capacity quickly to address customer demand, and housing developers want to address the social and political imperative to build more.

The headlines obsess over how much electricity AI will use. The real bottleneck is simpler: can the grid deliver power to the right place at the right time?

Power transmission you can’t use

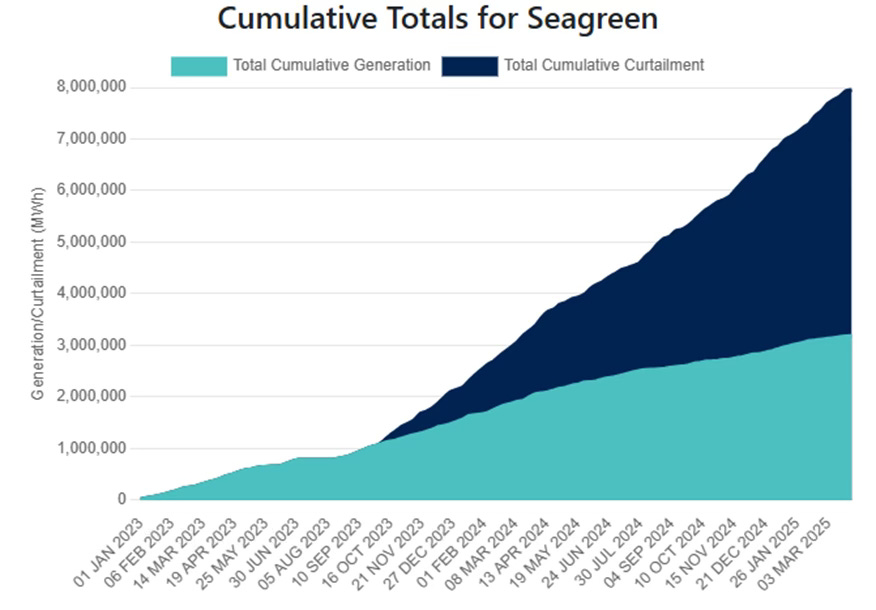

The UK built a lot of wind in northern Scotland while most demand sits in southern England. Moving that power south requires long-distance transmission, which is where congestion hits.

When there’s plenty of electricity but not enough transmission capacity, system operators turn down generators to avoid overloading lines - this is known as curtailment - and it’s expensive. The operator pays wind farms to reduce output and pays other units (often gas) to ramp via the Balancing Mechanism. These constraint costs flow to consumers.

An analysis of the two main Scotland / England transmission corridors (B4 / B6) suggests that £1.65BN of curtailment costs Jan 2024 to Apr 2025 could have been 25% lower if just an additional 500 MW more transfer capacity had been available. The reduced capacity was caused by planned upgrades so average usable capacity across the key boundaries sat around ~60% in 2024, with long stretches nearer ~40%. Congestion costs exploded as a result.

The timeline to increase capacity is long. New links were planned back in 2015, but are only expected to be completed in 2029.

Similar challenges exist in the US. Dominion Energy paused new data-center connections in 2022 due to transmission constraints, then later resumed with limits until new lines are in place (until a 500 kV reinforcement lands in 2026). In 2023, Virginia’s DEQ even floated a diesel-generator variance so data centers could keep running during grid stress while upgrades finished. These workarounds are common.

Clever workarounds

xAI became famous for how quickly it built its first Colossus data center, becoming the largest cluster in the world (~300 MW with 200k GPUs) in just 122 days. It also became infamous for using temporary gas turbines to generate power (some argued were illegally installed without permits) because of the lack of power capacity in Memphis, Tennessee.

Working around the long grid timelines with ad-hoc, on-site power generation seems to be part of the plan for Colossus 2. Even though Tennessee has refused to allow more gas generators, xAI has acquired a power plant over the border in Mississippi, deployed temporary power generators there, and connected them with medium voltage power lines.

The goal is to build a 1GW data center and the only way to do it quickly enough is to build your own power generation.

Can we build?

Building new capacity in a sustainable way is the biggest challenge faced by grid operators. The median wait for US interconnection is now 5 years (with 2.6TW in interconnection queues) and in the UK new applications have been paused. When the market is demanding new capacity, it’s inevitable that the workarounds are going to cause problems.

Which leaves the question: what actually fixes this?

For buyers, “cheap green kWh” is the wrong metric: contracts must include deliverability. Some will call for flexible compute so data centers can participate in demand response, but that’s mostly unworkable.

Governments should stop awarding mega-campus tax breaks before firm deliverability is secured. They should make any subsidy contingent on infrastructure improvements, like we’ve seen with Meta’s data center.

Near term, expect more self-provisioned power (often gas, because it’s dispatchable and financeable) while transmission and substations catch up. Long term, nuclear is a perfect fit with data center load profiles, as shown by Microsoft.

Whether incumbents (ISOs/TSOs and regulated utilities) remain in the critical path will come down to permitting reform. If not, large buyers will keep going around them.